Laurence of Arabia and Spaghetti Westerns

Laurence of Arabia and Spaghetti Westerns

The English film director David Lean’s epic masterpiece Lawrence of Arabia, nearly two years in the making, was beset with initial problems. The script had to be re-written. Marlon Brando turned down the lead role, so did Albert Finney. But when released in 1962, the film won an Oscar for Lean and made the young actor Peter O’Toole into a star.

Filmed in Jordan, Spain and Morocco, Lawrence of Arabia involved a demanding military-type operation. Working in desert or semi-desert terrain, a 400-strong team of actors, technicians and production staff needed a catering corps to feed them, accompanied by sleeping tents, equipment trucks, horse and camel handlers, plus vast quantities of food and water for the livestock.

After filming in Jordan from May 1961, the unit reassembled in Spain, where part of Seville doubled for Cairo, Damascus and Jerusalem, and many interior scenes were shot. But the most spectacular sequences were staged around Almeria. Production headquarters were established in the city’s bus station, and a 150-metre tramway was constructed in the Parque Nicolás Salmerón and the Parque José Antonio for Cairo scenes that were intercut with those filmed in Seville.

Over 400 horses were brought in from Jerez de la Frontera, Guadix, Seville and Madrid, while 150 camels were assembled from Morocco and various parts of Spain for the Aqaba episode. This required an elaborate reconstruction of the town that kept 200 locally recruited workers busy for three months. Built at Carboneras in a dried-up river bed on the Algarrobico beach, this remarkable set was in fact a cunning illusion, a series of carefully positioned facades that could only be filmed from one angle. Yet it represented an entire town, including a mosque and official buildings. Nearby was a Turkish camp with more than seventy tents, and several hundred Turkish soldiers took part in the defence of Aqaba. Most of the villagers of Carboneras were employed as extras.

In Cabo de Gata, sixty workers laid a 2.5 km railway track along which some 130,000 square metres of desert-simulating sand (raked smooth after each take) was shifted for the famous scene of the Arab attack on a Turkish train, led by a sword-brandishing Colonel Lawrence. The locomotive was transported in sections to the location by lorry. An international array of TV camera crews was on hand to cover this all-action sequence, but because of the danger to horses and extras it was decided not, as originally intended, to blow up the train. Instead it was derailed.

Other villages featuring in the film were El Alquián, Gergal, Nijar and Rodaiquilar. When the unit moved onto Morocco, the “oasis” created near the village of Tabernas with palm trees from Alicante, remained — and is still there as a souvenir of the four hectic months when David Lean and his associates put Almerla on the movie-making map. The actor Anthony Quinn is fondly remembered at the Los Cármenes del Zapillo bar, which he and his double frequented, and Eddie Fowlie, who constructed the oasis, stayed on to become proprietor of the El Dorado Hotel in Carboneras.

David Lean came back to Spain, but this time to Madrid and around Soria, to make “Dr Zhivago” (1965) and was about to return to Almeria as the setting for an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s novel “Nostromo” when he died in April 1991.

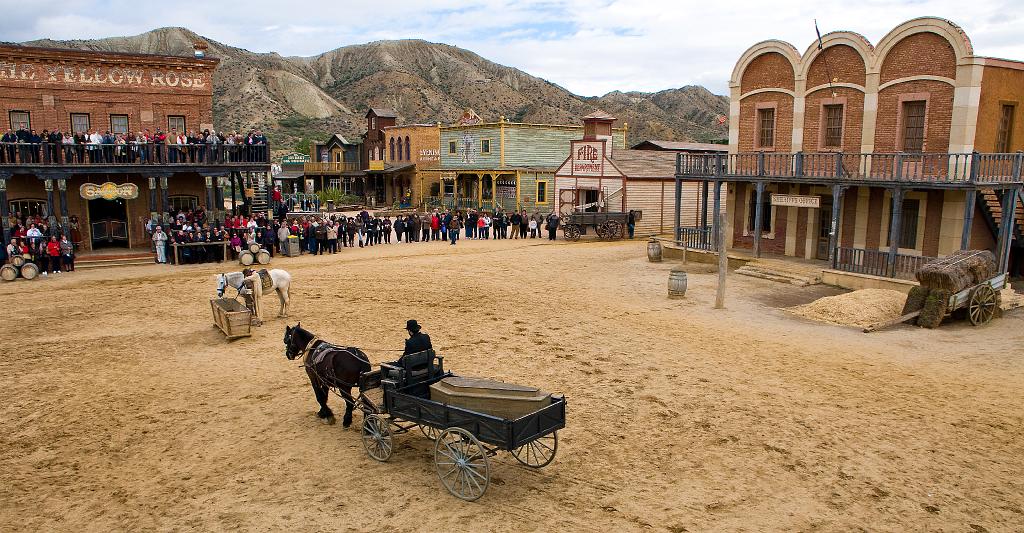

After Lawrence of Arabia had blazed the trail, other film makers were drawn to Almerla. During the 1960s Clint Eastwood, Lee Van Cleef, Charles Bronson, Brigitte Bardot and Raquel Welch, among others, were at work in the vicinity.

As many as nine films were in production at the same time and Sergio Leone directed his well- known spaghetti westerns The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and A Fistful of Dollars here.

The sun, brilliant light, an arid landscape resembling the Wild West of Arizona, and low labour costs kept the boom going for several years, but it eventually came to an end as production costs began to rise in Almerla and other, cheaper locations were found.

At Tabernas or “Mini Hollywood”, a replica Wild West town where more than 100 films were made, some Spanish veterans of those days still appear in a few movies and TV commercials, but mostly they performed for coachloads of package tourists, staging hold-ups and gunfights, or posing for photographs.

The fastidious, gentlemanly David Lean may have found this mass production sequel to his classy epic rather tatty, but it kept much needed cash flowing into Almeria until the 1970s. Its demise left a hole in the local economy that was ultimately filled by the amazing “plasticultura” boom of fruit, vegetables and flowers mass-produced under vast plastic tents.

The fastidious, gentlemanly David Lean may have found this mass production sequel to his classy epic rather tatty, but it kept much needed cash flowing into Almeria until the 1970s. Its demise left a hole in the local economy that was ultimately filled by the amazing “plasticultura” boom of fruit, vegetables and flowers mass-produced under vast plastic tents.